Volatility, Agility & Resilience: Next-Level Planning

Volatility, Agility & Resilience: Next-Level Planning

This is a combined and condensed summary of a series of best practice exchanges among supply chain directors on next-level planning. The contributions have been anonymised and generalised from their original, specific contexts to respect participants' privacy.

Improving forecast accuracy with machine learning

Allowing for different tolerances and categories, the typical scenario has been for 10-20% of SKUs to fall outside the forecast accuracy tolerance limit. This rate often doubled during the pandemic, generally not including availability-driven deviations. Across a wider sample of retail businesses who have implemented machine learning, the typical change has been from 40-60% accuracy using traditional methods to 70-90% accuracy with machine learning used to better understand drivers and lead demand indicators.

Determining drivers:

a common approach would be to take up to 200 potential drivers from 1000+ databases and overlay this with historical data so that the machine learning algorithms detect which drivers are most significant;

to predict in-store demand as lockdowns eased, for example, high frequency data like Google Map data of traffic to retail outlets by date, time and postcode were overlaid with other external data like the number of Covid cases by postcode, the level of restrictions and other data to build predictive models at granular and aggregate levels. This showed key differences between countries and regions where people responded slightly differently to their local conditions but enough to have had a material impact on demand;

for longer lead-time scenarios of 10+ weeks, for example, it may be that a different combinations of drivers and data points give better predictive power.

Critically, machine learning reduces the reliance on tacit knowledge and guesswork: typically, around 70% of drivers are already identified and being used in forecasts but around 30% are not or given a significantly different weighting in the predictive models which contributed to the improvement in forecast accuracy.

For businesses that have their own data science teams, open source platforms mean that proprietary algorithms can be combined with the out-of-the-box algorithms to further improve accuracy. It is also important to ensure the ML platform highlights the contribution of each different driver, turning the black box of AI transparent to increase trust in the output and, in turn, increasing adoption.

ML/AI is also starting to have a key impact in areas such as automating promo insights, baseline sales computation, competitor promo mapping, pricing effects and improving logistics scheduling / routing.

a common approach would be to take up to 200 potential drivers from 1000+ databases and overlay this with historical data so that the machine learning algorithms detect which drivers are most significant;

to predict in-store demand as lockdowns eased, for example, high frequency data like Google Map data of traffic to retail outlets by date, time and postcode were overlaid with other external data like the number of Covid cases by postcode, the level of restrictions and other data to build predictive models at granular and aggregate levels. This showed key differences between countries and regions where people responded slightly differently to their local conditions but enough to have had a material impact on demand;

for longer lead-time scenarios of 10+ weeks, for example, it may be that a different combinations of drivers and data points give better predictive power.

ML/AI-driven forecasting best practice

Data acquisition, preparation and transformation initially requires highly skilled human intervention as, without careful preparation, data cannot be effectively modelled to deliver the desired outcome variable.

Model selection is a critical step which also requires expertise as this is where ML/AI can make a real impact, particularly in so much that some tools can learn dynamically from the data, validate model performance and effectively converge models to deliver improved forecasting capability with minimal human effort. For example, in one FMCG company, deploying AI forecasting solutions also allowed for automation in rapidly building out product-level and supply chain insights (i.e. promo effects, waste...) as useful bi-products of the demand modelling.

However, an accurate forecast is only half the battle...you also have to be able to execute. Machine learning in forecasting can help model scenarios and impacts across all channels and so aid understanding of what needs to happen on execution to close the gap to plan and forecast. Similarly, it supports ‘intelligent post game analytics’ to understand what went wrong, where, and why.

Efforts to improve forecast accuracy and close the gap between plan and execution will be hampered if functions like finance, commercial and supply chain each have their own takes on what is and should be happening. Machine learning-enabled platforms that are able to evaluate multiple drivers from multiple data streams allows teams to express and test their views of the world to aid and improve mutual understanding and decision making.

ML/AI-driven demand forecasting can lead to greater complexity: it’s a trade off when trying to improve forecast accuracy as it often means a higher frequency of planning which introduces noise into the process. Consider automating processes around C-class SKUs and focus on managing deviations.

Case in point: Forecast accuracy and sales impact

One particular exchange centred on a question about the impact on sales for a 1% forecast accuracy improvement? This participant had established that a 3% improvement in OSA (on-shelf availability) prompted a 1% increase in sales but wondered about a similar metric for forecast accuracy.

The answer was essentially ‘it depends'. Taking the 3% OSA impact on sales as an example, intuitively it is understood that better OSA is likely to help sales. The baseline OSA and baseline sales level will impact the result. If OSA is poor then improvements have greater effect. As you get to higher levels of OSA then the effect on sales typically starts to diminish. It's not a linear effect.

The same is true for forecast accuracy: improving poor accuracy baselines can have a very positive impact on sales. But, similarly, when you get to higher levels of accuracy there are diminishing returns. But, it really depends on what you do with that increased forecast accuracy.

For example, if you take the improved accuracy and push that through the MEIO/safety stock calculations to reset inventory levels that can impact OTIF and therefore OSA. However, that has limits and most will experience a plateau here. If you are still executing based on forecast there will still be a chunk of that which is driven by error not accuracy. The effort required to further improve accuracy versus the gains received don't balance. That's also a challenge as corporate targets tend to accumulate year on year. What worked last year may not be enough for this year etc.

Other systematic approaches are needed to push through the limits that accuracy alone has. For example, what can you do with your end-to-end planning set up to increase service (OTIF, OSA etc) when increases in forecast accuracy are just not sustainable. Is this accuracy just at finished goods? What about upstream into the BOM's and BOD's?

Strategic buffers, proper decoupling and applying the right planning methods along the chain were also mentioned as ways to impact lead-times, agility, service level etc. which can positively impact sales potential. If increasing sales is THE strategic goal then several tactics are needed.

Demand sensing

Pandemic-driven volatility reduced reliance on historical data models and increased interest in real-time data including from external sources, often referred to as demand sensing.

Discussion participants tended to be using a blend of conventional forecasting (using ePOS and historical data) and demand sensing methods. This often prompted a ‘tsunami’ of data and challenges in distinguishing between signal and noise and in recalibrating the connection between lead demand indicators and consumer behaviour. This has been altered by the pandemic and is still a moving target. For example, determining whether the trend for home-based consumption displacing other channels is long-term or will eventually revert to pre-pandemic levels. Similarly, the impact of promotions has become harder to forecast and decompose into what’s actually driving any uptick…the promotion or other coincidental factors? However, there was (and is) a clear desire to further explore and improve demand sensing capabilities.

One illuminating case centred on how ticketed events were helping retail businesses in particular to improve their forecast accuracy. Most demand sensing data sources will incorporate publicly available data like public holidays and the weather but in-attendance / ticketed events can add another level and offer more granular and location-specific insights on likely demand patterns globally, regionally, nationally and locally. An initial pilot project evaluated the correlation between event types and demand, with the in-house team in conjunction with a third-party analytics provider. This had two main outputs: greater clarity in understanding the drivers of demand (which are already captured in seasonality adjustments) and improved forecast accuracy of between 0.2% - 2% as determined by the organisation’s existing accuracy metrics. As more data and forecasts were processed, the specific event types and properties which have the most impact on demand became even clearer. This is now being extended to non-ticketed events such as TV sports broadcasts which will have different implications for demand depending on multiple location-based factors. For unscheduled and inherently unpredictable events, it is possible to better grasp the impacts as and when they occur.

Closing the gap between plan and execution

“...the key to success is not about who makes the best forecast but about who is best able to respond to developments as they happen...”

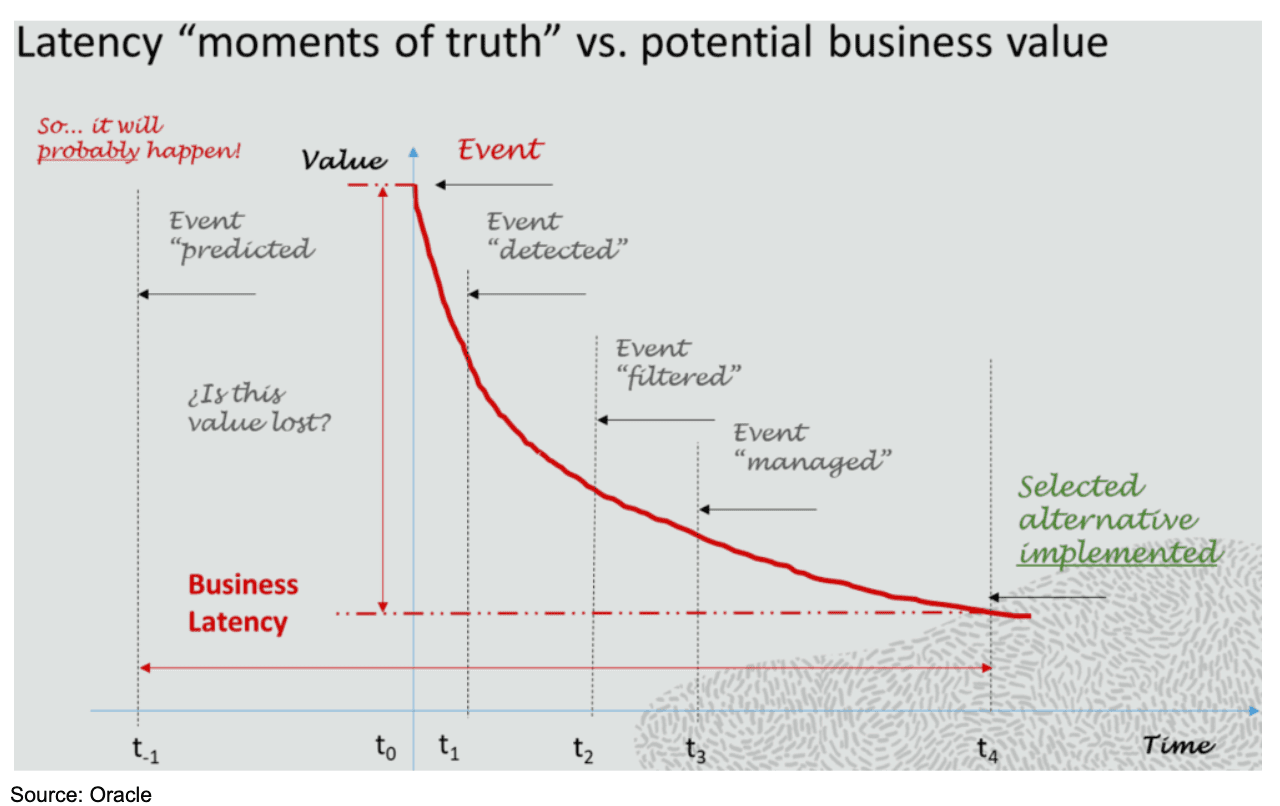

In other words, closing the plan-execution gap is about reducing the time lag or latency of deviations from plan being predicted and detected to being successfully managed.

Latency definition: the speed at which you can predict something is going to happen and execute a response to that event. Latency is a combination of data availability and process.

Latency t- (predictive)

Scenario planning is key to decreasing latency by creating a ‘playbook’ of responses which can be deployed at speed in contrast to working through the event from a standing start;

Demand sensing is another key part of the solution. In retail this can be social sensing which gives you a picture of what's happening amongst consumers that is about to affect demand. In a manufacturing context this could be about introducing sensors to monitor real time consumption. Or in logistics, it can be about getting information on supply chain disruption, e.g. issues at the ports.

Latency t+ (responsive)

The pandemic has pushed businesses towards short term decision making but the mid-term (S&OP) monthly horizon that will ultimately influences profitability. Translating from demand forecast to ordering required a reduction or elimination of silos and latency is most often caused by layers of hierarchy. Moreover, large businesses are often regionally siloed which tended towards a centralised decision making unit as regionally made decisions can affect other parts of the global business. Slower decision making was exacerbated when finance did not trust the plan number as much as its own financial forecast. To address this, there was a growing convergence of finance and supply chain, often referred to as ‘business partnering’, where finance specialists sat with the supply chain and planning teams.

Reducing latency best practice recommendations

A ‘whole organisation’ approach: IBP cannot just be a supply chain project…it must be integral and understood by all functions. The more senior the sponsorship, the better the chance of success;

A centre of excellence can be a good way to bring all the necessary elements together. The CoE should be made up of people outside of operational roles in order to be truly effective;

Adopting a design thinking approach to customer lifecycle management is a useful approach: this can help other functions better understand the value of supply chain in the context of the customer promise;

Cloud technology reduces latency by having fewer technology anachronisms: applications are up to date and are automatically maintained which reduces lag;

Low latency planning / IBP requires a business case. To do this, it can be valuable to look at what will happen if nothing is done; what are the costs to inaction?;

Do not over focus on a single instance platform across a large organisation. There can be multiple clouds and technology can interface.

Organisational structure & people emerging best practices

Of course, technology was not the only lever available for closing the planning-execution gap: organisation structure and process design either hindered or helped the flow of critical information and the capability for prompt, informed decisions to be taken. High performing organisations often demonstrated non-siloed structures whereby, instead of a traditional SCOR-based model, the focus is on end-to-end processes like IBP, O2C and increasingly omnichannel with process owners responsible for holistic optimisation.

Critical areas for best-in-class cross-functional alignment included product / service innovation, fulfilment, aftercare and planning. Increasingly, these teams have business partners who, for example, have both a deep, systematic understanding of supply chain operations and financial control to bridge those potential silos. These are often supported by Centres of Excellence, particularly for analytics which major on optimising segmentation, cost-to-serve and customer behaviour.

A key point for planners in particular was that it pays dividends not to confuse planning and execution and recognise that scheduling is not the same as planning...the latter requires particular skill sets around cross-functional communication in particular. Planners are likely to be more effective if they think and talk like business owners in terms of customer experience and profitability rather than a narrow focus on, for example, improving OTIF scores by a couple of points.

Non-sequential / concurrent planning

The traditional approach to supply chain planning is sequential i.e. collecting the demand picture first, then the supply and capacity planning perspective, before considering working capital and service level implications to ask whether the plan is feasible or whether we need to go back to sales to change the product mix etc. By the time all of this data is collected and processed, typically 30-days have passed.

Covid has meant that data collected at the beginning of the process has become completely meaningless by the time decisions need to be made. Non-sequential or ‘concurrent’ planning enables a view into an organisations’ entire planning network and aligns data so that a change in one part of the supply chain triggers corresponding changes and communications in the rest of the chain, in real time. It enables what-if scenarios so that organisations can understand their impact on their whole network and assess options before anything actually happens.

In times of high volatility with the situation changing almost on a daily basis, you need to be able to run scenarios on-demand. You can’t wait for an MRP weekend run before starting calculations the following week.

The S&OP/IBP process works within the concurrent planning framework so you can keep the same monthly cadence but, within that month, you have the ability to simulate the changes that are happening so that conversations are based on current data and, therefore, more productive. Concurrent planning becomes the enabler which adds greater dynamism and agility as it does not rely on using the last sync point of the underlying process. It is about having an ‘always on’, ‘always synchronised SC’ to answer key business questions you have to answer every day. It helps remove the silos so that you don’t have to run a cascaded asynchronous process to get the answers.

Concurrent planning isn't a monolithic process or technology but should be adapted according to the industry / supply chain archetypes (MTO, MTS etc.) and the existing levels of maturity related to data management, process centralisation & stability and collaboration with partners.

It's vital to define exactly what is meant by 'agility' among all stakeholders. There are three types of agility:

Faster decision-making, especially in response to disruption: for example, Lenovo was able to increase market share by responding faster to supply chain disruption

Shorter planning cycles: no matter what your maturity or cadence now, moving to shorter cycles will bring benefits even in industries like steel-making

Closing planning & execution gaps

Case study: BAT's implementation of concurrent planning

BAT started implementation of concurrent planning in 2019 and completes in Q1 2022:

Business case was stated in terms of both tangible benefits (e.g. working capital preservation including through better inventory control of higher value products) and intangible benefits (e.g. a better way of dealing with volatility and disruptions than manipulating Excel sheets)

All key cross-functional stakeholders including senior management spent a lot of time at the beginning to thoroughly define agility and what value they wanted to extract from concurrent planning

Planning is split into supply and demand teams. Supply planning is more centralised with 3 main global hubs (compared to spread over circa 100 country-based teams for demand planning) and, although more complex, had quite well established processes

Implementation has been phased across regions in nine deployment waves following an agile methodology where learnings from the first waves inform subsequent waves

Started with core planning and then expanding which could either further improving core planning or more focused on supplier collaboration

Already had good process at a short-term, tactical level supported by a control tower but wanted to integrate suppliers who now log in directly which enables scenario planning based on supplier data

Business case was stated in terms of both tangible benefits (e.g. working capital preservation including through better inventory control of higher value products) and intangible benefits (e.g. a better way of dealing with volatility and disruptions than manipulating Excel sheets)

All key cross-functional stakeholders including senior management spent a lot of time at the beginning to thoroughly define agility and what value they wanted to extract from concurrent planning

Planning is split into supply and demand teams. Supply planning is more centralised with 3 main global hubs (compared to spread over circa 100 country-based teams for demand planning) and, although more complex, had quite well established processes

Implementation has been phased across regions in nine deployment waves following an agile methodology where learnings from the first waves inform subsequent waves

Started with core planning and then expanding which could either further improving core planning or more focused on supplier collaboration

Already had good process at a short-term, tactical level supported by a control tower but wanted to integrate suppliers who now log in directly which enables scenario planning based on supplier data

Change management

As mentioned above, a critical first step is to thoroughly define agility among all stakeholders and have a clear understanding of what the desired improvements should be

Data management: BAT already had a global master data team and data stewards for governance. It took 3-4 years to establish mature processes from an already good base where the impact of different objects was well understood and different rules established according to their contexts

User adoption & process compliance: this was the highest priority KPI at BAT. Daily and weekly checkpoints were set to monitor adoption and compliance to understand which processes and workbooks were being used and when. This feedback helped fine-tune the processes and improve adoption

Don't touch: several participants mentioned analysis they had done that showed that as much as 70% of the manual touches in planning made no difference, either because they were too small or because, taken together over time, they cancelled each other out. This was a major focus for BAT who mandated a manual planning horizon of one week (instead of the typical 4-24 weeks) and compliance was reported to senior management. Once people began to see that the system helped them, process compliance reached 95%+

Centres of Excellence: a lot of emphasis was placed on leveraging key individuals who understood both operations and IT to help progress application support teams into truly cross-functional CoEs. Rather than a siloed approach of being referred to one application team or another, there was cross-application support and IT and subject-matter experts are able to speak the same language

Concurrent planning best practice

You can't (re)design a process independently of the technology that will enable it...it's like having a war strategy without knowing what weapons you have available;

Not everything can be captured by tools and systems: much effort has gone into supplier relationships to reinforce flexibility when required;

Improvements can be realised at all levels of maturity:

Less mature: simply connecting the data to better visualise it is a worthwhile first step. A quick win is being able to change the prioritisation of customer segments on the fly and immediately see the impacts on all horizons;

More mature: breaking down internal silos in planning;

High maturity: integrating supply chain partners and execution systems although this can be especially complex in organisations with multiple legacy systems in place;

It's also important to consider the timeliness and accuracy of intelligence feeding into planning systems;

One possible outcome from taking a concurrent planning approach is redefining planning roles so that, rather than defining and demand or supply planners, they become more like 'network planners' and can structure around aptitudes for short-term or longer-term planning.

Integrated Business Planning (IBP) best practices

Over a series of discussions supported by Oliver Wight, members discussed how their S&OP / IBP processes needed to be 'tuned up' to cope with the extraordinary circumstances experienced during the pandemic. Best practice was defined as three concurrent and linked processes:

The annual strategy development process sets the direction, goals and roadmaps for the long-term, which sets top down expectations. Strategic horizons varies by sector – e.g. aerospace sector and pharma have strategic horizons of up to 25 years, consumer goods may be 5 – 10 years, etc.

Medium-term managed through monthly IBP (/advanced S&OP), a holistic business management process used to optimise and re-optimise the strategy deployment ‘bottom up’ plan. Main focus is on 4 – 24 or 36 months horizon, on a rolling basis. Identifies gaps between bottom up and top down plan and finds gap closing solutions. IBP is not intended to manage the short term. As a monthly process it is not sufficiently dynamic.

Short-term managed through daily/weekly S&OE / S&O execution or Integrated Tactical Planning process designed to execute the IBP plan and manage short-term changes.

The annual strategy development process sets the direction, goals and roadmaps for the long-term, which sets top down expectations. Strategic horizons varies by sector – e.g. aerospace sector and pharma have strategic horizons of up to 25 years, consumer goods may be 5 – 10 years, etc.

Medium-term managed through monthly IBP (/advanced S&OP), a holistic business management process used to optimise and re-optimise the strategy deployment ‘bottom up’ plan. Main focus is on 4 – 24 or 36 months horizon, on a rolling basis. Identifies gaps between bottom up and top down plan and finds gap closing solutions. IBP is not intended to manage the short term. As a monthly process it is not sufficiently dynamic.

Short-term managed through daily/weekly S&OE / S&O execution or Integrated Tactical Planning process designed to execute the IBP plan and manage short-term changes.

The Oliver Wight template identifies 5 key elements:

Product or Portfolio Management Review (PMR) process – a cross-functional team works on the plan to deliver the portfolio strategy over the mid-term horizon – ie managing the project funnel, the product master plan including phased changes, the resource plan and the financial return of the portfolio plan;

Demand Management Review (DMR) process:

shaping demand through Sales & Marketing activities unconstrained by supply;

key is to align around main assumptions and activities which drive forecast numbers;

forecast error should be measured and tracked and root causes analysed;

should clearly communicate to the other reviews the assumptions underpinning the forecast number to build trust and understanding;

Supply Chain Management Review process:

develop the supply plan to support the product and demand plans;

supply plan to be based on demonstrated capabilities (in short-term) and planned future capabilities (over mid-term);

Integrated Reconciliation Review process to consolidate and quality control the rolling business plan, orchestrate scenario planning and prepare for the MBR

Management Business Review which should be chaired by the relevant executive team member.

Product or Portfolio Management Review (PMR) process – a cross-functional team works on the plan to deliver the portfolio strategy over the mid-term horizon – ie managing the project funnel, the product master plan including phased changes, the resource plan and the financial return of the portfolio plan;

Demand Management Review (DMR) process:

shaping demand through Sales & Marketing activities unconstrained by supply;

key is to align around main assumptions and activities which drive forecast numbers;

forecast error should be measured and tracked and root causes analysed;

should clearly communicate to the other reviews the assumptions underpinning the forecast number to build trust and understanding;

Supply Chain Management Review process:

develop the supply plan to support the product and demand plans;

supply plan to be based on demonstrated capabilities (in short-term) and planned future capabilities (over mid-term);

Integrated Reconciliation Review process to consolidate and quality control the rolling business plan, orchestrate scenario planning and prepare for the MBR

Management Business Review which should be chaired by the relevant executive team member.

How should supply chain be involved in IBP?

There was generally more divergence on this but, ideally, IBP should not be owned by supply chain but by the business unit owner. There is a tendency for this to ‘slide’ to the supply chain function because they want a formal process to generate a realistic plan and feel that commercial teams can be excessively aspirational/optimistic. Supply chain then becomes the constraining factor of ‘what could be possible’.

Similarly, supply chain should not be in the demand management review. It’s important for commercial teams to think about ‘how good could things get’ before considering supply constraints otherwise the gap is never made clear which means opportunities may be lost and/or supply constraints are not fundamentally addressed / taken as fixed. Supply chain may have input - perhaps by providing data on orders - but no seat. In smaller companies where people may have multiple roles, it’s vital that they remember which ‘hat’ they are wearing at each stage of the process.

Design the IBP process structure to reflect your organisation structure and decision rights. Create rules about empowerment boundaries and set down which numbers trigger escalation.

Engaging functions and building trust in the process

Create cross functional alignment by sharing assumptions behind the product, demand and supply plans, and working to improve assumption accuracy.

Tendency is to pull in all stakeholders: this can disenfranchise those who are responsible for managing the short term. Keep people to their competencies.

It is very important that the Exec team has a shared understanding of the IBP process and see it as their business management process. They own it and use it to make most key business decisions.

Product Management/Engineering/Marketing: position the PMR as their portfolio management meeting where they manage and align around the overall portfolio plan. Respect the product plan they publish. Choosing the right KPI’s for the PMR will build trust in the product plan – e.g. review past launches - have launches been on time before? If not, why not?

Sales & Marketing / Commercial: position the DMR as the management meeting for the commercial side of the business where they decide how they will deliver their commercial goals. One output should be the unconstrained demand plan and supply chain should comment afterwards around what it would take to deliver it.

Finance: they should be involved in all 5 steps of IBP, supporting the financialisation of the product/demand/supply plan, challenging where necessary and providing decision support.

Create cross functional alignment by sharing assumptions behind the product, demand and supply plans, and working to improve assumption accuracy.

Tendency is to pull in all stakeholders: this can disenfranchise those who are responsible for managing the short term. Keep people to their competencies.

It is very important that the Exec team has a shared understanding of the IBP process and see it as their business management process. They own it and use it to make most key business decisions.

Managing Volatility: Integrating S&OE with S&OP/IBP

Throughout the pandemic, it has been easy to become fixated on forecasting demand and so lose sight of end to end capacity and constraints. It's vital to take a broad view of risks and constraints under different scenarios and take a view on how much it is worth investing and where (e.g. bigger safety stocks, higher unit costs, extra capacity etc.). Without this integrated view, it often happens that one constraint is solved only for there to be another one right behind it.

In addition to the external volatility, there has also been an element of 'self-induced' volatility as a consequence of not properly understanding the knock-on effects of decisions.

Best practice is to formally integrate S&OE (aka Integrated Tactical Planning) with S&OP / IBP processes:

the starting point is the approved S&OP / IBP plan which needs to be disaggregated into weekly, daily or even hourly horizons by segment or line, depending on your cadence;

there should be a clear demand control process that is able to distinguish planned versus unplanned demand;

a formal regular / weekly capacity review serves as the handshake between planning and manufacturing and / or procurement and gives better awareness of constraints and bottle necks that may need to be mitigated;

it is critical to establish your Time Fence i.e. where the cost to respond to change in demand is significant. This helps prioritisation and allocation when cost to respond to change is higher and clearly understood.

critically, there should clear policies on acceptable safety stocks and on how to deal with deviations...what qualifies as a legitimate emergency requiring intervention, whose decision is it? This avoids each case being escalated and tying up time and attention;

at the S&OE level, there will be fewer options and those options are usually more expensive but these learnings about options and costs need to be proactively fed into the S&OP / IBP cycle so that there's an accurate understanding of context at this level and due consideration can be given to whether to invest in generating more / better options. There needs to be a continuity of understanding and a defined handover of long term into short term;

there should be clear roles, responsibilities, empowerment boundaries, escalation paths, integration measures and feedback loops. Holding firm to roles and responsibilities when under pressure is challenging, especially in relatively low headcount companies where the same people may have roles to play in the short-term and medium-term management processes;

keep people to their competencies – empowered middle managers managing the short-term according to the rules of engagement and senior leaders managing the strategic horizon. If there is a person with multiple ‘hats’, they must wear their ‘demand hat’ in the Demand Review and their ‘supply hat’ in the Supply Review.

in the face of uncertainty, try to refine inputs into the demand plan and, where the facts run out, discuss and agree assumptions. Focus on what has changed each month and what you can do to influence demand. Consciously decide which demand plan changes can be accommodated so that we protect the time fence.

use ‘available to promise’ functionality and/or good communication with suppliers to ensure reliable order promises to customers. Differentiate our handling of ‘normal’ orders which match the demand plan and ‘abnormal’ orders which we were not expecting. This includes regular and honest conversations with suppliers and partners.

Getting (and staying) close to suppliers, partners and customers

It's important to consider whether suppliers have enough information to be able to respond to our needs and plan for the longer term. In return, suppliers can often be excellent sources of information about what is happening in the world and what risks are present as they tend to have a bigger picture view.

The pandemic-driven experience has highlighted the lack of visibility for higher tier suppliers so this should form a part of the conversation with direct suppliers... even if you are not affected by capacity squeeze, they may well be.

There has been much discussion of dual sourcing but this is often not a realistic option. Especially when this is the case, it's important to be / become your suppliers' best customer through engagement and support:

engagement should be honest in the sense that not everything should always be the highest priority or seek to secure supply through pressure tactics;

sharing plans and making commitments further out means suppliers have more incentive and ability to meet those requirements. It's common to hear complaints about the lack of information coming from suppliers but part of that is about making it as easy as possible for them to supply the necessary information to feed into decision-making.

At the other end, there ought to be good communication among the customer service / commercial teams about who to prioritise and focus on making reliable promises to customers even if that cannot be their first preference. This might also include an integrated product review where, for example, priority might be given to lower margin products which are more reliable. When options on the supply side are limited, there may be levers on the customer side such as the timing of campaigns and prioritisation / rationalisation of SKUs.

A complex but potentially very useful approach would be demand analytics to understand the transferability of demand between SKUs to generate more options in handling short term volatility.

Scenario planning best practice

Understand trade-offs and stick to decisions at the business level;

Commercial and finance should be involved so that clear choices about trade-offs can be made and decisions backed up;

The process can begin with supply chain describing a range of possible scenarios and actions that could be taken in response - with associated costs and implications for customers - but finance and commercial teams need to be involved so that trade offs are understood at a business level;

Volatility is inherently unpredictable so often events will occur that no scenario will have envisaged but it's likely that you'll at least be closer to the right response by virtue of having had conversations around scenarios and constraints;

Transparency is key so getting accurate and timely data and being able to project scenarios within a system easily and quickly is important otherwise time is wasted discussing what the picture is rather than what could be done about it;

Also, factor in human behaviour and the tendency to build in some margin to forecasts, especially if that influences allocations…people are naturally inclined to look after their corner of the business. It's vital to have an environment where assumptions can be challenged and tested;

Codify assumptions which means turning thoughts into numbers, for example, by quantifying how supplier terms may change and what it might cost to secure supply under certain scenarios;

When a business is in survival mode, it can be difficult to find time for these conversations with the right people involved but the alternative is time being taken up in an inefficient way because any time a planner and a commercial team member don't agree, the dispute is escalated. It is worth taking the time up front to understand what uncomfortable decisions and trade offs need to be made and have the resolve to stick with those decisions to reduce the energy spent on these tactical battles;

Of course, emergencies happen and urgent action needs to be taken but, soon after, it's vital to start planning the recovery.

What has worked for discussion participants to manage the balance between S&OE & S&OP?

Dedicated focus on reinforcing S&OE, often by centralising and formalising roles and escalation / de-escalation processes and triggers;

Demand managers aggregate the demand but product managers (with P&L responsibility) decide which segments, customers and products to prioritise;

S&OP meetings sometimes had longer horizons up to ten years;

Ensuring that VPs are not in S&OE meetings and ensuring trust in the process and good communication up to S&OP and Executive S&OP meetings, which should really be approving recommendations already made;

Significant investment in dashboards and tools for improving transparency between SC and commercial teams, including scenario modelling using digital twins;

Combining a single, best-guess target alongside a range of possible outcomes to encourage discussion about contingency plans;

Globalisation of production assets so different regions can flex and support each other

SKU rationalization, often driven by SC teams.

What challenges remain?

Short-term volatility delaying longer-term decision-making which may end up having greater consequences;

How to maintain the discipline of focus between S&OE and S&OP meetings, particularly in lower headcount businesses where often the same people are involved

who owns each process?;

how should senior management be optimally involved?;

How to get buy-in from commercial teams who are often reluctant to reduce SKU offering?

Digital Transformation of Supply Chain Planning

Digital transformation has been on corporate agendas for some time already but, borne of necessity, tangible progress accelerated significantly since 2020. A silver lining of the pandemic may be that the business case is clearer so the focus has shifted towards implementing and scaling digitalisation initiatives.

Supply Chain Design Modelling and Analytics

Supply chain network (re)design used to come around every few years or so, often based on quite a high level view of customer segments and associated costs. Now, competitiveness and even business continuity relies on the capability to dynamically adapt network flows based on a much more granular understanding of cost drivers.